Jacob Bradley

12 comments

12 comments

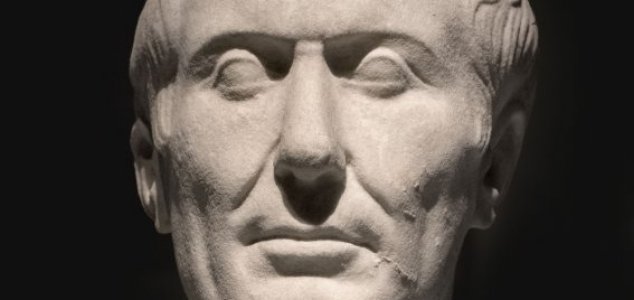

Image Credit: CC BY 2.0 Angel M. Felicisimo Few lives have so captivated history like the life of the great Julius Caesar. One of the defining battles of the general-turned-dictator's career was the Battle of Pharsalus, in which he claimed a dominant victory over his arch-rival in the Roman Civil War, Pompey the Great. However, many historians overlook a rather peculiar incident that occurred on the morning of the battle, as recorded by the historian Plutarch:

"Then, during the early morning watch ... a great light blazed out over [Caesar's] camp, and a flaming torch arose out of this light and fell upon Pompey's camp..."1

Plutarch went on to say that Caesar himself attested to the truth of this account, having apparently seen the event himself as he was checking on his camp sentries. The above account is from Plutarch's biography of Pompey, but he would go on to repeat the exact same account in his biography of Caesar. A similar telling of this event was also provided by the ancient historians Appian and Lucan.

Later that day, Caesar would go on to crush Pompey's forces, sealing the fate of his former ally. In light of that, we are left wondering what exactly happened that morning. What was the "great light" and the "flaming torch" that Caesar saw?

Roman Omens

Contemporaries of Caesar and Pompey would no doubt have seen the event as an omen, some sign that ultimately pointed to Caesar's impending victory. Omen-watching was incredibly prolific in Ancient Rome, and practices such as haruspicy (divination via entrails) and augury (divination via the flight patterns of birds) were well-known. Caesar himself was Rome's Pontifex Maximus at the time of this event, making him one of Rome's highest-ranking religious figures and putting him in a position to be well-acquainted with various forms of omen-watching and divination. Surely he was seeking a favorable sign prior to his final showdown with Pompey, not only for his own benefit, but for that of his soldiers, who had fought a grueling campaign alongside their leader up to this point.

Understanding the religious sensibilities of Romans of Caesar's era helps to underscore the importance of seeing a favorable omen prior to a major engagement. Not only that, but the peculiarity of this event gave Caesar a great opportunity to receive the omen positively. Unlike the aforementioned divination practices of haruspicy and augury, which often had relatively set interpretations of various observations, we have no evidence that such set interpretive guidelines were in place for unusual and/or unexpected phenomena. Therefore, Caesar had a certain freedom to view the strange event as predicting a favorable outcome for his side in the upcoming battle. When such an observation was relayed to his troops (assuming they hadn't all already seen the event for themselves), this almost certainly gave Caesar's tiring troops a very important morale boost prior to battle, which may very well have tipped the scales. In short, the strange event provided Caesar with the ability to declare a (potentially self-fulfilling) prophecy of victory.

Something in the Weather?

The lingering mystery is this: what, then, actually was the light and torch that Caesar witnessed, beyond just an ostensible omen?

From the account, we can discern that the basic flow of events went something like this: a "great" light (meaning either exceptionally large, exceptionally bright, or perhaps both) rose from Caesar's camp, before either transforming into something resembling a blazing torch, or having that split from within itself. The object resembling a blazing torch then somehow travelled (presumably through the air) the moderate distance between the two camps, though still within sight of Caesar's camp, before descending upon the Pompeian camp.

This stands as a very bizarre account, to say the least. If something like that were witnessed today, many would likely classify it as a "meteorological phenomenon." In fact, the event does bear some degree of similarity to a few known phenomena of that sort, namely light pillars, ball lightning, and St. Elmo's fire.

Regarding light pillars, they perhaps most-closely resemble the image of a blazing torch moving through the sky, with their shape being that of a vertical pillar of light, which one could feasibly compare to a torch. They also fit the time of day in which the event occurred, as they generally occur when the sun is near the horizon, as it could have been during Caesar's early-morning patrol of his sentries. However, the notion of the sighting being that of a light pillar does not account for how it began as a great light, before becoming a blazing torch, or how it managed to move horizontally over a moderate distance. Additionally, light pillars are dependent upon ice crystals to form, and the Battle of Pharsalus took place in early-August, in western Greece.

Looking to ball lightning, that oft-utilized "get out of jail free card" for attempting to explain away a variety of different atmospheric occurrences, it could be understandably used to explain the motion of the light in question, but fails to account for the "blazing torch" shape. Also, to this very day, there is not a scientific consensus (or anything close to one) regarding what ball lightning actually is, so to attribute it definitively to an event from over 2,000 years ago would be problematic at best.

As for St. Elmo's fire, this is a phenomenon that has been widely attributed to various events in the ancient world, and it could account for the "great light" rising from Caesar's camp and perhaps for the light in Pompey's camp as well. However, the shoe is not a perfect fit here, and it doesn't account for the significant horizontal movement that the light in question displayed.

While each of those three phenomena has some passing resemblance to an element of the occurrence witnessed by Caesar, none seem to perfectly fit the account.

Something... Else?

In addition to these more mainstream understandings, the world of folklore and mythology provides us with some additional types of phenomena which resemble the occurrence in question. Most notably, there are some similarities between the moving lights that Caesar witnessed and the will-o'-wisps and alike from folklore around the world. If the answer to this mystery cannot be located within the realm of accepted phenomena, perhaps it can be found in the stories preserved by our ancestors?

Source:

Plutarch. Roman Lives: a Selection of Eight Roman Lives. Translated by Robin Waterfield, Oxford University Press, 2011. Comments (12)

Caesar's torch

June 28, 2020 | 12 comments

12 comments

Image Credit: CC BY 2.0 Angel M. Felicisimo Few lives have so captivated history like the life of the great Julius Caesar. One of the defining battles of the general-turned-dictator's career was the Battle of Pharsalus, in which he claimed a dominant victory over his arch-rival in the Roman Civil War, Pompey the Great. However, many historians overlook a rather peculiar incident that occurred on the morning of the battle, as recorded by the historian Plutarch:

"Then, during the early morning watch ... a great light blazed out over [Caesar's] camp, and a flaming torch arose out of this light and fell upon Pompey's camp..."1

Plutarch went on to say that Caesar himself attested to the truth of this account, having apparently seen the event himself as he was checking on his camp sentries. The above account is from Plutarch's biography of Pompey, but he would go on to repeat the exact same account in his biography of Caesar. A similar telling of this event was also provided by the ancient historians Appian and Lucan.

Later that day, Caesar would go on to crush Pompey's forces, sealing the fate of his former ally. In light of that, we are left wondering what exactly happened that morning. What was the "great light" and the "flaming torch" that Caesar saw?

Roman Omens

Contemporaries of Caesar and Pompey would no doubt have seen the event as an omen, some sign that ultimately pointed to Caesar's impending victory. Omen-watching was incredibly prolific in Ancient Rome, and practices such as haruspicy (divination via entrails) and augury (divination via the flight patterns of birds) were well-known. Caesar himself was Rome's Pontifex Maximus at the time of this event, making him one of Rome's highest-ranking religious figures and putting him in a position to be well-acquainted with various forms of omen-watching and divination. Surely he was seeking a favorable sign prior to his final showdown with Pompey, not only for his own benefit, but for that of his soldiers, who had fought a grueling campaign alongside their leader up to this point.

Understanding the religious sensibilities of Romans of Caesar's era helps to underscore the importance of seeing a favorable omen prior to a major engagement. Not only that, but the peculiarity of this event gave Caesar a great opportunity to receive the omen positively. Unlike the aforementioned divination practices of haruspicy and augury, which often had relatively set interpretations of various observations, we have no evidence that such set interpretive guidelines were in place for unusual and/or unexpected phenomena. Therefore, Caesar had a certain freedom to view the strange event as predicting a favorable outcome for his side in the upcoming battle. When such an observation was relayed to his troops (assuming they hadn't all already seen the event for themselves), this almost certainly gave Caesar's tiring troops a very important morale boost prior to battle, which may very well have tipped the scales. In short, the strange event provided Caesar with the ability to declare a (potentially self-fulfilling) prophecy of victory.

Something in the Weather?

The lingering mystery is this: what, then, actually was the light and torch that Caesar witnessed, beyond just an ostensible omen?

This stands as a very bizarre account, to say the least. If something like that were witnessed today, many would likely classify it as a "meteorological phenomenon." In fact, the event does bear some degree of similarity to a few known phenomena of that sort, namely light pillars, ball lightning, and St. Elmo's fire.

Regarding light pillars, they perhaps most-closely resemble the image of a blazing torch moving through the sky, with their shape being that of a vertical pillar of light, which one could feasibly compare to a torch. They also fit the time of day in which the event occurred, as they generally occur when the sun is near the horizon, as it could have been during Caesar's early-morning patrol of his sentries. However, the notion of the sighting being that of a light pillar does not account for how it began as a great light, before becoming a blazing torch, or how it managed to move horizontally over a moderate distance. Additionally, light pillars are dependent upon ice crystals to form, and the Battle of Pharsalus took place in early-August, in western Greece.

Looking to ball lightning, that oft-utilized "get out of jail free card" for attempting to explain away a variety of different atmospheric occurrences, it could be understandably used to explain the motion of the light in question, but fails to account for the "blazing torch" shape. Also, to this very day, there is not a scientific consensus (or anything close to one) regarding what ball lightning actually is, so to attribute it definitively to an event from over 2,000 years ago would be problematic at best.

As for St. Elmo's fire, this is a phenomenon that has been widely attributed to various events in the ancient world, and it could account for the "great light" rising from Caesar's camp and perhaps for the light in Pompey's camp as well. However, the shoe is not a perfect fit here, and it doesn't account for the significant horizontal movement that the light in question displayed.

While each of those three phenomena has some passing resemblance to an element of the occurrence witnessed by Caesar, none seem to perfectly fit the account.

Something... Else?

In addition to these more mainstream understandings, the world of folklore and mythology provides us with some additional types of phenomena which resemble the occurrence in question. Most notably, there are some similarities between the moving lights that Caesar witnessed and the will-o'-wisps and alike from folklore around the world. If the answer to this mystery cannot be located within the realm of accepted phenomena, perhaps it can be found in the stories preserved by our ancestors?

Source:

Plutarch. Roman Lives: a Selection of Eight Roman Lives. Translated by Robin Waterfield, Oxford University Press, 2011. Comments (12)

<< Previous story

Spring is here and we have nowhere to go

Spring is here and we have nowhere to go

Next story >>

Why did I choose the Tarot?

Why did I choose the Tarot?

Other World News

United States and the Americas

Palaeontology, Archaeology and History

Spirituality, Religion and Beliefs

Total Posts: 7,777,049 Topics: 325,469 Members: 203,893

Not a member yet ? Click here to join - registration is free and only takes a moment!

Not a member yet ? Click here to join - registration is free and only takes a moment!

Please Login or Register to post a comment.