Space & Astronomy

January 3, 2019 · 28 comments

28 comments

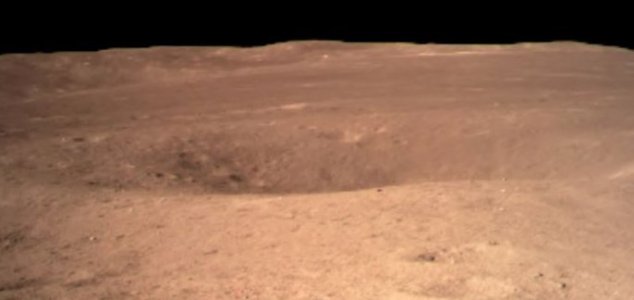

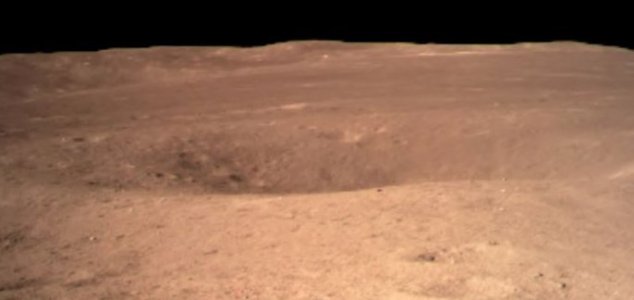

This image reveals, for the first time, an unexplored region of the Moon's far side. Image Credit: CNSA

During its time there, the probe will take samples and explore the immediate vicinity with a rover. By analyzing the surface material, it is hoped that it can also learn more about the Moon's formation.

For China however, the success of the mission is as much political as it is scientific.

"There's a lot of geopolitics or astropolitics about this, it's not just a scientific mission, this is all about China's rise as a superpower," said defense analyst Malcolm Davis.

"There's a lot of enthusiasm for the space program in China. There's a lot of nationalism in China, they see China's role in space as a key part of their rise."

It is believed that China currently intends to land humans on the Moon by the year 2030.

If that's true, we could see a whole new space race take shape over the next few years.

Source: The Guardian | Comments (28)

First ever image from Moon's far side revealed

By T.K. RandallJanuary 3, 2019 ·

28 comments

28 comments

This image reveals, for the first time, an unexplored region of the Moon's far side. Image Credit: CNSA

China's Chang'e 4 spacecraft has made history by being the first ever to touch down on the far side of the Moon.

Hailed by China's state-run media as a giant leap for human space exploration, the mission saw a successful touchdown in the South Pole-Aitken basin - an impact crater 2,500km in diameter.During its time there, the probe will take samples and explore the immediate vicinity with a rover. By analyzing the surface material, it is hoped that it can also learn more about the Moon's formation.

For China however, the success of the mission is as much political as it is scientific.

"There's a lot of enthusiasm for the space program in China. There's a lot of nationalism in China, they see China's role in space as a key part of their rise."

It is believed that China currently intends to land humans on the Moon by the year 2030.

If that's true, we could see a whole new space race take shape over the next few years.

Source: The Guardian | Comments (28)

The Unexplained Mysteries

Book of Weird News

AVAILABLE NOW

Take a walk on the weird side with this compilation of some of the weirdest stories ever to grace the pages of a newspaper.

Click here to learn more

Support us on Patreon

BONUS CONTENTFor less than the cost of a cup of coffee, you can gain access to a wide range of exclusive perks including our popular 'Lost Ghost Stories' series.

Click here to learn more

Israel, Palestine and the Middle-East

Ancient Mysteries and Alternative History

Other World News

Russia and the War in Ukraine

Total Posts: 7,768,284 Topics: 325,021 Members: 203,765

Not a member yet ? Click here to join - registration is free and only takes a moment!

Not a member yet ? Click here to join - registration is free and only takes a moment!

Please Login or Register to post a comment.